Speaker: Luka Ostojic @LukaO

Speaker: Luka Ostojic @LukaO

Affiliation: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

Affiliation: Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb

Title: ‘We were not ready’: Impact of Required Reading on Negative Perception of Adolescence

Abstract (long version below): In this paper we discuss long-term effects of school required reading on adolescent readers. Secondary school reading is a part of the personal and social initiation that influences how pupils perceive both literature and themselves. To learn more about this, we will analyze the results of the qualitative empirical research conducted on a large national sample of non-professional readers (1.000 participants older than 18). We strongly focus on negative self-perception which was manifested when participants discussed their adolescent immaturity. It will be demonstrated that required reading plays an important, but not a necessarily positive role in the initiation process.

Long abstract

Long abstract

Both young adult literature and secondary school required reading have their target audience in common. But while the YA literature is closely related to its adolescent readers (through content, promotion, and reception), the link between required reading and its readers is neither as clear, nor as researched. The required reading lists in the West consist mostly of famous works of Western Canon and national literature, but it is hard to find a meaningful relation between differing works, formal education goals and adolescent living experience. Academic research of required reading provides few answers as aesthetic education is rarely in academic focus. So, although numerous pupils are obligated to go through chosen works of literature, the long-term effect of the reading process remains a mystery. This paper is an attempt to open a discussion on that underestimated topic.

If we observe adolescence as a process of initiation into the adult status, the secondary education plays an important mediating role, and so does required reading which provides guidance about the general culture which should be appreciated by the adult members of the society. Adolescence is thus seen as a liminal space where pupils are both old enough to enter the realm of “serious” literature, but too young to completely grasp its value. These are not essential characteristics of adolescence, but socially accepted ideas which are also embedded into the education process. School reading is thus framed as a part of the personal and social development that influences how pupils perceive both these works of literature and their own identity. This paper aims to investigate how this model manifests itself in practice, more precisely what former pupils still perceive years after graduation.

We aim to answer that question by analyzing the results of empirical research on a large national sample of non-professional readers (1.000 participants older than 18). The research was conducted through semi-structured interviews: participants were obliged to choose from three to five literary works that they were impressed with the most, that they remember the best and that they personally consider important. The interview revolved around the chosen works, and it concluded with a few general questions, one of them being about the personal experience of the school required reading.

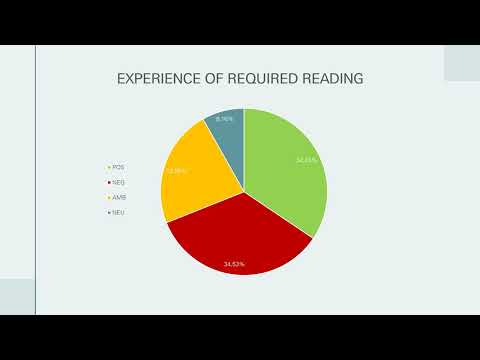

The quantitative analysis of interviews will illustrate the general attitude towards the required reading experience, taking into account differences between participants in age, gender, academic degree and place of education. It will additionally measure the impact of specific canonical works of literature commonly present on the required reading lists. The analysis will point out the level of correlation between the general attitude on required reading (positive, negative or ambivalent) and the equivalent attitude about specific works. Finally, we will focus on the negative self-perception, as around 20% of participants directly discussed their personal or collective inability to comprehend required reading because of their immaturity. This number is relatively high considering the fact that participants were not directed to discuss this particular topic.

The quantitative and qualitative analysis of this sub-sample will lead us to three possible explanations for this phenomenon. The simplest one is that the initiation process was unsuccessful. The participants were unable to establish a relation to the chosen texts and therefore they could not learn to appreciate the wider “adult” culture, alienating themselves from aesthetics in general.

The second explanation points out a more complex relation between readers and texts. A significant number of participants mentioned their immaturity while addressing reading, interpretation and education problems which essentially had nothing to do with their age. It seems that the immaturity narrative served as a coping mechanism which explained away their problematic relation with the school assignments, but eventually led to diminishing stereotypes about adolescents and to an uneasy relation with the canonical literature.

Finally, a group of participants eventually managed to establish a positive relation to required reading near the end of their schooling, more precisely with works of realism and modernism. While it is plausible that participants were indeed mature enough to enjoy these works, it should be noted that these works resemble contemporary culture formally, thematically and linguistically.

In the end we can conclude that required reading plays an important, but not necessarily positive role in the initiation process. The question remains how to encourage a meaningful relation between adolescent readers and “serious” literature.

This paper will be based on theories from fields of ethnology, critical pedagogy, sociology and literary theory, as interdisciplinary approach is deemed necessary both to understand this topic and to frame the large amount of qualitative and quantitative data provided from the aforementioned research.

References

Altieri, Charles. 1984. “An Idea and Ideal of Literary Canon”. Canons. Ed. Robert von Hallberg. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press: 41-65.

Bourdieu, Pierre, et al. 2000. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Felski, Rita. 2008. Uses of Literature. New Jersey: Wiley.

Koopman, Constantin. 2010. “Art and Aesthetics in Education”. The SAGE Handbook of Philosophy of Education. Ed. Richard Bailey, Robin Barrow, David Carr & Christine McCarthy. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Ltd: 435-451.

McCallum, Robyn. 2002. Ideologies of Identity in Adolescent Fiction. New York & London: Garland Publishing.

Montgomery, Heather. 2009. An Introduction to Childhood. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Quantz, Richard A., Terry O’Connor and Peter Magolda. 2011. Rituals and Student Identity in Education: Ritual Critique for a New Pedagogy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.