Speaker: Alysse Baker @abaker

Speaker: Alysse Baker @abaker

Affiliation: Roanoke College

Affiliation: Roanoke College

Co-authors: Elizabeth Cohen (West Virginia University)

Co-authors: Elizabeth Cohen (West Virginia University)

Title: Parasocial Compensation or Enrichment? Investigating the Relationship Between Age, Loneliness, Parasocial Relationships and Eudaimonic Motivations Through The Lens of Socioemotional Selectivity Theory

Abstract: Drawing from social compensation explanations for parasocial relationships (PSRs) and socioemotional selectivity theory, this study examined whether the effect of age on the development of PSRs is moderated by loneliness or a greater desire for meaningful or eudaimonic media experiences. Participants (N = 409) of various ages completed an online survey. Results show that PSR strength was negatively related to age, and this effect weakened with greater levels of reported loneliness, but only among those who reported low to moderate loneliness. Eudaimonic motivations were positively related to PSR strength but did not moderate the effect of age on PSR strength. .

Long abstract

Long abstract

Parasocial relationships (PSRs) are feelings of familiarity and closeness that people can develop with fictional characters and other media figures (Horton & Wohl, 1956). There is a long-standing conversation in scholarship on parasocial experiences about whether these

these pseudo-relationships are motivated by a need to compensate for social deficiencies or unmet social needs (Tsao, 1996). Findings on whether PSRs are associated with negative indicators of social well-being such as loneliness have varied (e.g., Rubin et al., 1985; Wang et al., 2008). However, current research on the compensatory role of PSRs has adopted a refreshingly nuanced explanation for seemingly inconsistent past findings. As Stein et al. (2024) recently demonstrated in an experiment comparing responses to parasocial and social relationships, PSRs did not affect relatively stable, trait-like assessments of loneliness, but they did improve situational states. This suggests that the PSRs can play a compensatory role, but with limits. PSRs do not provide a “remedy for all-encompassing feelings of loneliness,” but they can be used to improve people’s mood states in ways that mirror some benefits of reciprocal social relationships (p. 578).

There is relatively little research on older adults’ parasocial relationships. However much of the research that does exist has tended to adopt a social compensation lens by, for instance, examining how negative life indicators (e.g., loneliness) are associated with PSRs (e.g., Bernhold & Metzger, 2020; Chory-Assad & Yanen, 2005; Eggermont & Vandenbosh, 2001; Lee & Park, 2017; Lim & Yanen, 2005; Perloff & Krevens, 1987). This common focus on age, loneliness and PSRs may be rooted negative myths about older adults. Older adults are stereotyped as being relatively more lonely than other age groups, but this is not true (e.g., Dykstra, 2009). Evidence suggests that older adults are typically less lonely than younger adults (e.g., Barreto et al., 2020; Australian Psychology Society, 2018). Thus, if PSRs can alleviate some feelings related to isolation (Stein et al, 2024), younger people may be relatively more motivated to develop these relationships than older people.

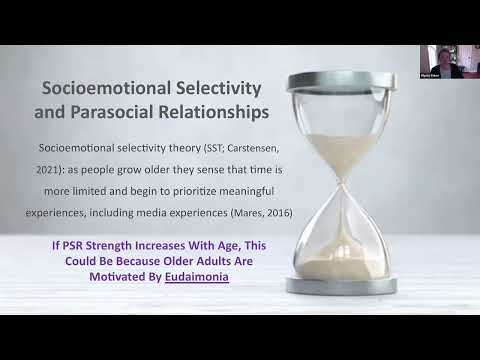

Nonetheless, there is a reason to expect that PSRs might increase with age. Socioemotional selectivity theory (SST; Carstensen, 2021) explains that as people grow older they sense that time is more limited and begin to prioritize positivity and meaningful experiences in their personal relationships. SST also explains how people’s media choices change with age. For instance, Mares et al. (2016) showed that compared to younger adults, older adults found more meaning in media that offered feelings of warmth, while younger adults found more meaning in more suspenseful content. In other words, age may be positively associated with eudaimonic motivations for media use (e.g., seeking meaning and personal growth), including the development of parasocial relationships.

In this study, we reexamine the relationship between PSRs and age through the lens of SST. Participants completed an online survey that asked them to identify a fictional or non-fictional media figure with whom they felt close. With this person in mind, they answered questions about their PSR, loneliness, and motivations for media consumption. Participants were recruited from several places (MTurk, Facebook, and University classes) to increase the age diversity of the sample. The final sample consists of 409 participants, with ages ranging from 18 to 82 (M = 34.82, SD = 18.22).

Partial correlations (controlling for gender) show that age is unrelated to loneliness and eudaimonic media use motivations, but age was negatively related to PSR strength. Eudaimonic motivations were positively related to PSR strength. Results of a double moderation PROCESS analysis showed that loneliness—but not eudaimonic motivations, moderated the effect of age on PSR strength. Increases in loneliness were associated with reduced effects of age on PSR strength, but only among participants who reported low to moderate levels of loneliness (about 50% of the sample). In other words, respondents developed less intense PSRs with age. However, increases in loneliness diluted this effect and it was significant only for those who were generally less lonely.

These findings complicate existing assumptions about the role of parasocial relationships across the lifespan. Younger people were relatively more likely to develop PSRs than other people, but this effect was only significant for individuals with low to moderate levels of loneliness. This is quite possibly because PSRs can provide a compensatory function to those experiencing lower levels of loneliness, but they are insufficient to meet the needs of those who experience higher levels of loneliness. This is consistent with recent research suggesting that PSRs may be able to alleviate situational social discomfort but not more substantial social impoverishments. Finally, because eudaimonic motivations were positively associated with PSR strength regardless of age, these results do not support an SST explanation for older adults’ PSR relationship development.

References

Barreto M., Victor C., Hammond C., Eccles A., Richins M. T., Qualter P. (2021). Loneliness

around the world: Age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences. Redirecting

Bernhold, Q. S., & Metzger, M. (2020). Older adults’ parasocial relationships with favorite

television characters and depressive symptoms. Health Communication, 35(2), 168-179. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1548336

Carstensen, L. L. (2021). Socioemotional selectivity theory: The role of perceived endings in

human motivation. The Gerontologist, 61(8), 1188-1196. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab116

Chory-Assad, R. M., & Yanen, A. (2005). Hopelessness and loneliness as predictors of older

adults’ involvement with favorite television performers. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 49(2), 182-201.

Dykstra, P. A. (2009). Older adult loneliness: Myths and realities. European Journal of Ageing,

6, 91-100. Older adult loneliness: myths and realities | European Journal of Ageing

Eggermont, S., & Vandebosch, H. (2001). Television as a substitute: Loneliness, need intensity,

mobility, life-satisfaction and the elderly television viewer. South African Journal for Communication Theory and Research, 27(2), 10-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02500160108537902

Lim, C. M., & Kim, Y. K. (2011). Older consumers’ TV home shopping: Loneliness, parasocial

interaction, and perceived convenience. Psychology & Marketing, 28(8), 763-780.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20411

Lee, M. S., & Park, J. (2017). Television shopping at home to alleviate loneliness among older

consumers. Asia Marketing Journal, 18(4). "Television Shopping at Home to Alleviate Loneliness Among Older Consumers" by Min-Sun Lee and Jihye Park

Mares, M., Bartsch, A., & Bonus, J. A. (2016). When meaning matters more: Media preferences

across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 31(5), 513-531. APA PsycNet

Perloff, R. M., & Krevans, J. (1987). Tracking the psychosocial predictors of older individuals’

television uses. The Journal of Psychology, 121(4), 365-372.

Rubin, A. M., Perse, E. M., & Powell, R. A. (1985). Loneliness, parasocial interaction, and local

television news viewing. Human Communication Research, 12(2), 155-180.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1985.tb00071.x

Stein, J. P., Liebers, N., & Faiss, M. (2024). Feeling better… But also less lonely? An

experimental comparison of how parasocial and social relationships affect people’s well-being. Mass Communication and Society, 27(3), 576-598. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2022.2127369

Tsao, J. (1996). Compensatory media use: An exploration of two paradigms. Communication

Studies, 47(1-2), 89-109. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510979609368466

Wang, Q., Fink, E. L., & Cai, D. A. (2008). Loneliness, gender, and parasocial interaction: A

uses and gratifications approach. Communication Quarterly, 56(1), 87-109.