Speaker: Jana Lüdtke @jluedtke

Speaker: Jana Lüdtke @jluedtke

Affiliation: Freie Universität Berlin

Affiliation: Freie Universität Berlin

Title: Once Upon a Rime: What Effect do Textually Encoded Emotions Have on Readers?

Abstract (long version below): The project focuses on the cultural-semiotic concept of Emotion Potential (cf. Schwarz-Friesel 2017) and examines the predictive power of textually encoded emotions to evoke reader emotions, particularly within literary texts. Using the ChildTale-A corpus (Herrmann & Lüdtke, 2023), six sub-studies analyze emotions felt by readers across 18 Grimms fairy tales, categorized as negative, neutral, or positive. Initial findings from sub-studies 1-3 reveal that textually encoded emotions indeed predict felt emotions. Consistent with the general negativity bias (cf. Norris, 2019), effects are stronger for negative tales. While 13% of variance at text level is explained, high inter-stimulus and inter-reader variability demand further subsequent analyses.

Long abstract

Long abstract

Recently Herrmann and Lüdtke (2023) presented a quantitative approach to investigate textually encoded emotions Grimms’ Children’s and Household Tales. The authors apply manual annotation at the sentence level to determine the texts’ emotion potentials in a core set of 80 German fairy tales (ChildTale-A). Annotations happened on the dimension’s valence and arousal (cf. Russel, 1980) as well as for six discrete emotions (Ekman, 1990). The authors reported four measures representing different features of textually encoded emotion. For example, Average Valence (AV), the mean of the valence annotations for all sentences of a fairy tale, represents the overall emotional tone. Emotion Potential (EP), the proportion of sentences categorized as positive or negative (according to their valence annotations), indicates to what extent a fairy tale is emotionally encoded.

The aim of the project presented here is to investigate the predictive power of textual encoded emotions in eliciting reader emotions. In doing so six different studies are planned to collect readers’ evaluations about their emotional reactions when reading fairy tales classified as negative, neutral, or positive (according to their textual encoded emotions). The combination of the results of all studies should allow to test different hypotheses. First, we assume a positive relation between textual emotions and felt emotions. Following cultural-semiotic concept of textual Emotion Potential (cf. Schwarz-Friesel 2017; Winko 2022.) textually encoded emotion should predict emotions felt by readers, both at sentence and text level. Therefore, readers should be more likely to report negative emotions when they read negative fairy tales, and positive emotions when they read positive fairy tales, and non or both positive and negative emotions when reading neutral fairy tales (hypothesis 1). Following the concept of negativity bias, which suggests that negativity has a stronger impact than positivity (Baumeister et al., 2001; Norris, 2019), we additionally hypothesize a higher similarity between felt and textually encoded emotions for fairy tales and sentences classified as negative, compared to those classified as neutral or positive (hypothesis 2) . In this contribution, initial analyses at the text level are reported.

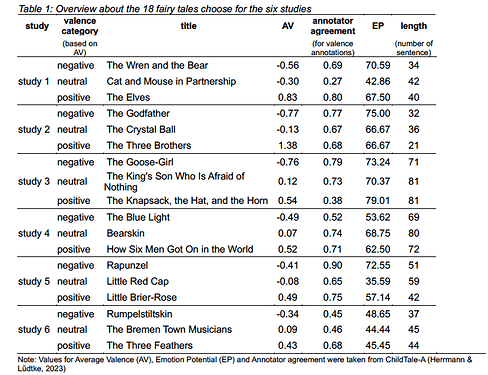

Selected fairy tales

Based on the AV reported in ChildTale-A, one negative, one neutral and one positive fairy tale were selected for each of the six studies. The total sample of 18 fairy tales encompasses both well-known and lesser-known fairy tales like Little Red Cap or the The Crystal Ball, varying in length and annotator agreement for valence annotations (see Table 1).

Procedure

In each of the six studies, every participant read three fairy tales in random order. Readers were explicitly instructed not to evaluate the emotions described in the text, but rather their own emotions felt while reading. For each fairy tale, participants read the entire text, providing evaluations for felt valence, six different discrete emotions, liking, and comprehensibility. Subsequently, the fairy tale was presented again, sentence by sentence. After each sentence, participants indicated their felt valence and the occurrence of discrete emotions.

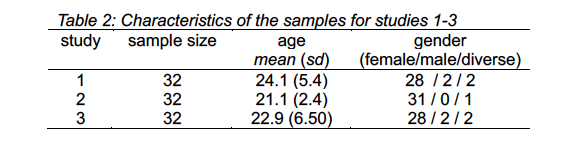

Sample

Until now data collection for the first three studies are finished. Table 2 presents a brief overview of the first three samples. All participants are native German speakers and receive course credit for their participation.

Results at text level

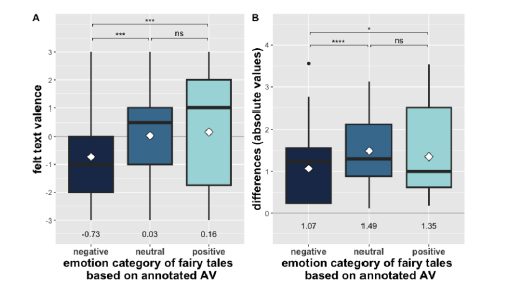

To test the first hypothesis, felt text valence is compared to fairy tales annotated with emotion categories negative, neutral, and positive. As depicted in Figure 1 Part A, felt text valence for negative fairy tales is significantly more negative compared to felt text valence for neutral and positive fairy tales (tneg-neutr(125) = -3.81, p<.001, tneg-pos(125) = -4.18, p<.001), whereas the difference between neutral and positive fairy tales is not significant (tneut-pos(125)<1). To test the second hypothesis, the absolute difference values between felt text valence reported by each participant and the annotated AV of the fairy tale were computed. Figure 1 Part B illustrates that the difference was significantly smaller for negative and neutral fairy tales (tneg-neutr(125) = -4.44, p<.0001, tneg-pos(125) = -2.49, p=.043). The difference values between positive and neutral fairy tales do not differ significantly.

Figure 1

Part A depicts felt text valence values for fairy tales annotated as negative, neutral, or positive (based on Average Valence (AV)), Part B shows differences between felt text valence values and text AV for fairy tales annotated as negative, neutral, or positive. Results of pairwise t-tests (with Bonferroni, correction) are reported above, and mean values per category (white diamond) are reported below the boxplots.

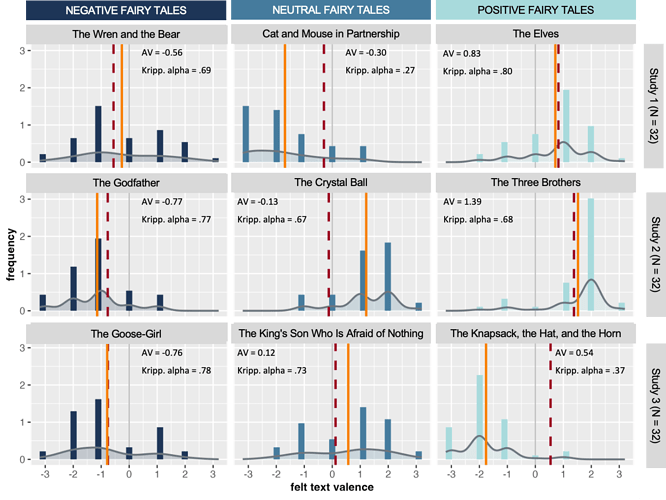

Figure 2 shows the distributions of the felt text valence ratings for each fairy tale separately. For all three negative fairy tales, the mean values for felt valence are negative and close to the AV taken from ChildTale-A . In contrast, only for two of the three positive fairy tales, the mean values for felt valence are positive; the mean felt valence for the positive fairy tale from sub-study 3 is negative. For the neutral fairy tales, the mean for felt valence is negative for one fairy tale, slightly positive for a second one, and clearly positive for a third one.

Figure 2:

Distributions of felt text valence for each of the nine fairy tales from sub-study 1-3. The red dotted vertical lines represent the Average Valence (AV) for each fairy tale based on ChildTale-A and the corresponding Krippendorfs’ alpha (Kripp. alpha; Herrmann & Lüdtke, 2023). The orange vertical lines represent the mean value for the felt text valence ratings.

Discussion

The analysis of felt valence ratings at the text level initially supports the assumptions of hypotheses 1 and 2. Textually encoded emotions, as reported in ChildTale-A, predict emotions induced in readers. On average, negative fairy tales induced more negative feelings compared to neutral and positive ones. Moreover, the differences between the AV taken from ChildTale-A and the felt text valence reported by readers are smallest for negative fairy tales. A simple linear regression predicting felt text valence ratings with AV is significant (F(1,356) = 56.96, p<.0001) but explains only 13% of the variance in the felt valence ratings. The distributions of felt valence ratings indicate considerable differences between different fairy tales but also between readers. To better understand the relationship between textually encoded emotions and felt emotions, more fine-grained analysis at the sentence level is planned. One question is whether individual reader profiles can be identified for different (types) of fairy tales.

References

Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5:4, 323–370, doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323

Ekman, P. (1992). An Argument for Basic Emotions. Cognition & Emotion, 6:3-4, 169–200. doi: 10.1080/02699939208411068

Herrmann, B. & Lüdtke, J. (2023). A Fairy Tale Gold Standard. Annotation and Analysis of Emotions in the Children’s and Household Tales by the Brothers Grimm. Zeitschrift für digitale Geisteswissenschaften, 8. doi: 10.17175/2023_005

Norris, C. J. (2021). The negativity bias, revisited: Evidence from neuroscience measures and an individual differences approach, Social Neuroscience, 16:1, 68-82. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2019.1696225

Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39:6, 1161. doi: 10.1037/h0077714

Schwarz-Friesel, M. (2017). Das Emotionspotenzial literarischer Texte. In A. Betten, U. Fix, and B. Wanning (eds.): Handbuch Sprache in der Literatur. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 351–370. doi: 10.1515/9783110297898-016

Winko, S. (2022). Literature and Emotion. In G.L. Schiewer, J. Altarriba, & B.C. Ng, (eds.). Language and Emotion: An International Handbook, Volume 3 (pp. 1417-1436), Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. doi: 10.1515/9783110795486-004