Speaker: Tracy Moniz @tmoniz

Speaker: Tracy Moniz @tmoniz

Affiliation: Mount Saint Vincent University

Affiliation: Mount Saint Vincent University

Title: Narrative matters: Exploring end-of-life care through the writings of physicians, patients, and caregivers

Abstract: We explore the significance of narratives in medical education, focusing on quantitative and qualitative research that highlights the impact of narratives on empathy training, end-of-life care situations, and moral residue experiences (i.e., a common experience among healthcare professionals and other moral agents when they perceive their own failure to meet moral requirements, despite others’ tendency not to blame them). Four papers present research conducted with the aim of reshaping the use of narrative in medical education. They describe the impact of fiction and nonfiction-labeled literary narratives, various types of narrative engagement, first-person narratives, fiction seminars, and transformative reading interventions.

Long abstract

Long abstract

With the global aging population, the focus on end-of-life care has intensified. With this comes a need to better understand the experiences of patients, informal caregivers, and physicians. Empathetic care requires a shared understanding of illness and its meaning. The narratives of each group offer a distinct perspective on end-of-life clinical experiences, yet comparative research is uncommon. This research compares public discourses on end-of-life care by these groups.

An archive of 332 first-person written narratives about end of life published over a decade (2010-2019) was created through searching public domains (e.g., national newspapers), personal blogs, and academic and literary journals in Canada. A qualitative comparative narrative analysis was conducted for patterns of content (e.g., theme) and strategy (e.g., characterization).

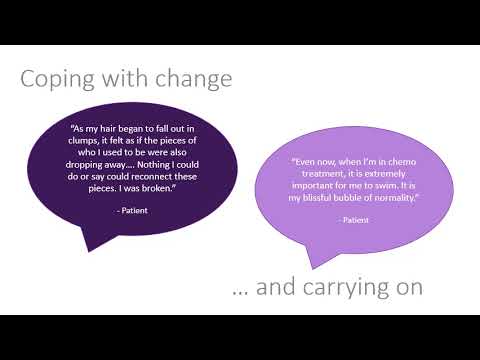

All groups wrote about feeling gratitude. Patients also emphasized coping with change and carrying on. Caregivers further focused on grieving loss, and physicians most often wrote about valuing humanism. Physicians were most likely to ascribe agency to someone (i.e., patients) or something (i.e., death) other than themselves and to decenter themselves in the story. Patients and physicians most often positioned the patient as the main character, while caregivers were as likely to focus the story on themselves as on the patient. Physicians were most likely to describe death as a source of tension, while patients and caregivers described the illness experience. Physicians and caregivers often wrote testimonies, while patients wrote quests.

Narrative research can illuminate unique aspects of end-of-life care. While death is a shared experience, each group approaches it differently. The disconnects have potential consequences for how end of life is experienced—whether patients’ values are honored, whether caregivers receive support, and whether physicians experience burnout. We need to foster learning experiences that integrate these unique perspectives into medical education, including leveraging the affordances of studying written narratives toward this end.