Speaker: Marijn Koolen @MarijnKoolen

Speaker: Marijn Koolen @MarijnKoolen

Affiliation: 1 Huygens Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2 DHLab, KNAW Humanities Cluster, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Affiliation: 1 Huygens Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands 2 DHLab, KNAW Humanities Cluster, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Title: How can online book reviews validate empirical in-depth fiction reading typologies?

Abstract (long version below): Online book reviews offer a valuable large-scale resource for studying how books affect readers. We verify whether the findings of empirical typologies of in-depth fiction reading apply to online book reviews. We ask whether the same linguistic characteristics that typify in-depth reading experiences apply to online Dutch book reviews and whether the poetics of reading differ across reviewing platforms and across reviewers. A corpus of 634,607 online Dutch book reviews from seven platforms is probed. Results show reviews across different platforms are similar in their distributions of syntactic features and all types of word groups related to sentiment, cognition, space, time and motion, but textual characteristics of online reviews change in relation to length, corroborating previous findings (Fialho, 2012).

Long abstract

Long abstract

Online book reviews offer a valuable large-scale resource for studying how books affect their readers, as reviews are unobtrusive observations of readers voicing their opinions and describing their experiences. At the same time, we might suspect they may be influenced by the kinds of platforms on which reviewers write and publish these reviews.The possibility of receiving responses or likes and dislikes means that people may adapt what they say to how they want to be perceived by others. For example, if they have a negative opinion of a popular book, they may express it less forcefully than when they are positive about it, or they may decide not to publish a review at all.

Studying the impact of books on readers is a complex and big topic, which requires a multidisciplinary perspective, with step-by-step procedures. In this paper, we are particularly interested in verifying whether the findings of empirical phenomenological reading typologies of in-depth fiction reading also apply to online book reviews of Dutch readers. To this date, several phenomenological reading typologies have been articulated, including Miall & Kuiken’s literary response typology (1995); Kuiken and colleagues’ self-implication typologies (Kuiken, Miall, & Sikora, 2004; Sikora, Miall, & Kuiken, 2011) and Fialho and colleague’s experiential and self-transformative reading typologies (Fialho, Miall, & Zyngier, 2011, 2012; Fialho, 2012, 2023 forthcoming). Common to these typologies is the nature of the in-depth reading experiences collected, where readers are free to comment as much as they like on their experiences of evocative passages. On the one hand, the nature of these in-depth reading experiences sharply contrasts with the nature of (shorter) online book reviews, which gives us a good opportunity to verify the validity of empirical typologies. On the other hand, if we find the same characteristics that have helped differentiate phenomenological reading types, this would allow us to argue that the lessons learned from the considerable body of experimental reader studies can be applied in the study of reviews. The second corollary here is that reviews give us the opportunity to study the impact of reading on a much larger scale than was previously possible. But whereas the analysis of dozens of interviews is mostly done manually, the analysis of hundreds of thousands of reviews calls for an algorithmic approach to study the linguistic characteristics related to theories of reading.

To this purpose, our guiding research questions are: (1) Do the same linguistic characteristics that help typify reading experiences in in-depth phenomenological studies of reader response also apply to online Dutch book reviews? (2) Does the poetics of reading (i.e., how readers talk about fictional books) differ across reviewing platforms? If so, how does it do they differ and how are they related to the different characteristics of the platforms? (3) Do reading experiences characteristics differ across reviewers; i.e., can we differentiate between reviewers giving their opinions, reviewers projecting experiences onto general readers, and reviewers describing their own experiences?

2. Methods and data

In this paper we make a first step in investigating how we can address these overarching research problems. We use a corpus of 634,607 online Dutch book reviews from seven different platforms. To study the differences between platforms and between reviewers, we analyzeanalyse reviews in terms of syntactic properties, affective and emotional language use and the use of pronouns and verbs. In previous research, tThe use of pronouns and verbs were found to differentiate reading types (Fialho, 2012).

2.1 Data and Resources

The reviews were crawled in multiple phases in the period 2013–2022 and cover a period of 23 years. The oldest review was published on 13 January 1999 and the most recent on 21 July 2022. They were written by a set of 226,927 reviewers who reviewed these books with potentially a diverse set of motivations. Some reviewed a book on a commercial platform to inform potential other buyers about the book as a product. Others reviewed a book on a social book cataloguing platform to share their opinion and join discussions of other readers. Yet others may have written their reviews more for themselves as personal reflection.

2.2 Preprocessing and Feature Analysis

We extract various linguistic features from large sets of online book reviews and discussions to investigate differences between platforms and reading types. We parsed all reviews with the Trankit parser (Nguyen et al. 2021) and processed the parse trees using the Dutch Reading Impact Model (Boot and Koolen 2020) to identify expressions of reading impact in review sentences.

2.3 Comparing reviewers and platforms

For the quantitative comparison of review characteristics of different platforms and reviewers, we analyse the fraction of review words that belong to certain word groups, e.g. affective terms, personal pronouns and verbs. For each of these groups, we assume that the number of words in a review that belong to that group follows a Poisson distribution. That is, we model the rate at which a reviewer chooses a word from that group as a Poisson process.

Because different reviewers may use different rates or an individual reviewer may use different rates for different reviews, there is rate heterogeneity, that is, there is variance in the λ parameter of the Poisson process. As a result, a Negative Binomial — representing a mixture of Poisson processes with different means — is a better fit for such word fraction distributions. In the analyses, a feature’s mean fraction is taken as the parameter for the negative binomial distribution. We compare platforms and reviewers by comparing their mean fractions.

We also include a qualitative comparison. In corpus statistics, qualitative comparison between subsets of texts is often done using a keyness measure to indicate to what extent a word or word group is more strongly associated with a certain subset than with the rest of the corpus (Gabrielatos 2018). A commonly used and robust keyness measure is the Log-Likelihood Ratio (LLR, Dunning 1993). By ranking the words in the reviews of a platform by LLR, the words most strongly associated with each platform can be qualitatively compared.

3. Results - Differences Between Platforms

Our findings are that reviews across different platforms are very similar in terms of their distributions of syntactic features and all types of word groups related to sentiment, cognition, space, time and motion.

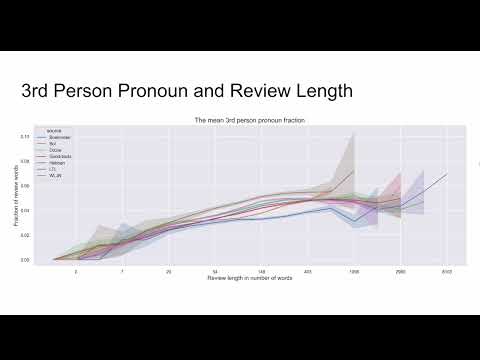

We find that the textual characteristics of online reviews change according to reviewwith their length. Short reviews focus on evaluation and persuasion, while longer reviews contain more discussion of the story, characters and the writing as well as the reader’s experience and opinion, which corroborate some previous findings of in-depth reading experiences (Fialho, Zyngier, & Miall, 2011, 2012). In longer reviews, some reviewers take an outside perspective and mainly use the third person, while other reviewers tend to focus more on their personal experience, and switch perspectives from first to second person to describe how they are drawn into the story world and how their experience blends with that of the story’s characters, analogous to the findings of Fialho (2012).

These findings have consequences for understanding how review platforms influence the content of reviews, but also for the study of reading fiction, which so far was based on small-scale interview studies. Our results align with those of interview studies, which suggests that online book reviews can be used to scale up the analysis of how books affect their readers.