Speaker: Lena Wimmer @LWimmer

Speaker: Lena Wimmer @LWimmer

Affiliation: University of Freiburg, Germany

Affiliation: University of Freiburg, Germany

Co-authors: Anita Körner, Luise Ende, and Ralf Rummer

Co-authors: Anita Körner, Luise Ende, and Ralf Rummer

Title: Higher Instead of Lower Accessibility of Fiction Texts Increases Epistemic Vigilance During Reading

Abstract (long version below): People evidently acquire inaccurate information when reading fiction, possibly due to low epistemic vigilance. We examine the prediction that low accessibility of fiction texts increases epistemic vigilance. We also explore associations of accessibility with transportation, foregrounding, and accepting fiction-based inaccuracies as accurate. N = 102 students were randomly assigned to read a fiction story either high or low in accessibility, after which foregrounding, transportation, and accepting fiction-based information were collected. High instead of low accessibility increased epistemic vigilance. Furthermore, accessibility was unrelated to transportation, and negatively linked with foregrounding. Accepting inaccurate information was not considered due to a floor effect.

Long abstract

Long abstract

Empirical evidence shows that humans acquire both accurate and inaccurate information contained in works of fiction (for an overview see Rapp et al., 2014). We define (in)accurate information by means of (in)congruence with general world knowledge. According to models of reading comprehension (e.g., Cook & O’Brien, 2014), readers monitor text content for such inaccuracy, but also for semantic discrepancies between different information units within the text. Here, we subsume both, inaccurate information and semantic within-text discrepancies, under the umbrella term ‘semantic inconsistencies’. Epistemic vigilance is a process thought to be involved in fiction-based acquisition of semantically inconsistent information (Consoli, 2018) and will lead to longer reading times for detected compared to undetected inconsistent information.

We carried out the current experiment to, first, test Consoli’s (2018) central assumption that reading a comparatively inaccessible fictional story is associated with higher levels of epistemic vigilance than reading a comparatively accessible fictional story. Second, we explored the associations of accessibility with transportation and perceived effects of foregrounding. Third, we explored whether accessibility is related to accepting fiction-based inaccuracies as accurate, as indicated by the performance in a general knowledge test.

This experiment was pre-registered at the Open Science Framework, see OSF. A total of 102 psychology students participated (91 females and 11 males; aged 18 to 45 years, MAge = 22, SDAge = 4). Participants were randomly assigned to one of two text versions, high or low in accessibility. The low accessibility text presented a rather recently published translation of an excerpt from Homer’s Odyssey by Lempp (2010; 4628 words). The high accessibility text (5853 words) was a “stylistically […] simplified variant of [this] translation” created by Thissen et al. (2022, p. 835). Both texts were modified to contain two types of semantic inconsistencies, namely inaccurate information and semantic within-text discrepancies: first, we inserted 18 inaccurate/accurate statements based on general knowledge norms by Tauber et al. (2013), von Aster et al. (2006), and Wertgen and Richter (2023). Second, we modified 18 statements to be discrepant to/matching earlier read story content. Each participant received half of each type of statements in the inconsistent and the other half in their consistent version. After the reading task, participants answered a translated version of the foregrounding scale by van Peer et al. (2007) and the transportation scale by Appel et al. (2015). Participants then answered 20 general knowledge questions in an open answer format. Of the 20 terms asked for, 10 had been mentioned in the text, 5 in their inaccurate version and 5 in their accurate version, and the remaining 10 were filler items.

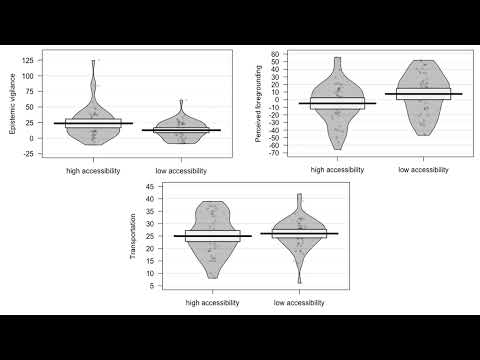

To test our hypothesis, a pre-registered one-tailed t-test for independent samples was conducted, with story accessibility as the independent variable and the epistemic vigilance score as the dependent variable. The epistemic vigilance score was calculated as reading time per syllable (of target and associated spillover sentences containing semantically inconsistent information) minus reading time per syllable (of target and associated spillover sentences containing semantically consistent information). The t-test was not significant, t(78.85)=2.71, p=.996, d=0.54. This was followed up with an exploratory two-tailed t-test, which revealed a significant difference in epistemic vigilance depending on accessibility, t(78.85)=2.71, p=.008, d=0.54. Importantly, the group difference contradicted the expected direction as participants reading the low accessible text on average demonstrated lower levels of epistemic vigilance than participants reading the highly accessible text. Three further t-tests for independent samples with story accessibility as the independent variable were carried out. The dependent variables were perceived effects of foregrounding, transportation, and accepting inaccurate information. The two text versions differed in perceived foregrounding, t(100)=2.37, p=.020, d=0.47, such that the highly accessible text was found to invite lower levels of foregrounding than the low accessible text. In contrast, there were no significant differences between the two text versions for transportation, t(100)=0.70, p=.48, d=0.14. In terms of accepting inaccuracies from the story, descriptive statistics were indicative of a floor effect (i.e., a total of three false alarms were observed across the entire sample). Hence, inferential statistics were not computed.

Finally, we explored bivariate Pearson’s correlations of epistemic vigilance with first, perceived effects of foregrounding, r(100)=-.25, p=.009, and second, transportation, r(100)=-.09, p=.35.

While our data does not allow clear conclusions regarding the influence of accessibility on the acceptance of inaccurate information, we offer new insights to the connection of underlying processing mechanisms while reading fiction texts (differing in accessibility). Taken together, we provide evidence that high fiction text accessibility, though linked with reduced foregrounding and unrelated to transportation, increases rather than decreases a proxy of epistemic vigilance. The relationship between foregrounding, epistemic vigilance, and reading comprehension deserves targeted investigation in the future. Based on our results, one could assume that the acquisition of inaccurate information can be reduced by high text accessibility due to high epistemic vigilance.