Speaker: Andrew Currie @AndrewC23

Speaker: Andrew Currie @AndrewC23

Affiliation: University of Strathclyde

Affiliation: University of Strathclyde

Title: Autistic Traits and Spatial Imagery in Literary Narrative Reading

Abstract (long version below): This paper presents a new approach to understanding the contributions spatial comprehension and spatial phenomenology, realised through spatial imagery, makes to literary narratives. As an innovation, it suggests looking at specific processing traits found in neurodivergent populations and comparing them to neurotypical populations. For the purposes of the paper, it considers the strengths that some autistic individuals have in producing visuo-spatial imagery, as well as differences readers show in generating spatially coherent scenes in memory and internal scene construction. These traits will be considered in relation to the experience of narrative absorption and other related subjective states.

Long abstract

Long abstract

Theoretical Background

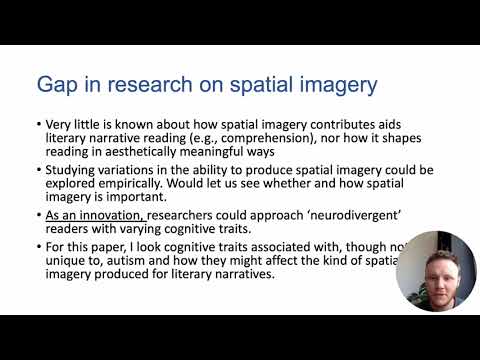

Spatial imagery, defined as the way we imagine spatial relations, locations, and movement (Blajenkova, Kozhevnikov and Motes, 2006), forms an important part of narrative processing. For example, there is evidence indicating that our ability to imagine future and fictious events depends, in part, on detailed internal scene construction (see Maguire, Vargha-Khadem and Hassabis, 2010; Pearson 2019), which likely relates to how we mentally construct scenes for literary narratives (see Jajdelska et al. , 2019). There is also evidence showing that readers frequently track spatial changes as part of the situation models they form for texts. (Zwaan and Oostendorp, 1993), and use spatial representations to connect situation models causally (Jahn, 2004)

Some researchers have also suggested that spatial descriptions in texts can also play a phenomenological role. For example, they can cause an increase in the sense of presence — i.e. the sense of perceptually ‘being there’ in a fictional world — that readers feel (Kuzmičová, 2014; Pianzola et al. , 2021); and that egocentric (first-person) and allocentric (third-person) spatial frames can affect immersion, such that reading a narrative from a first-person perspective can be considered more immersive for readers (Hartung et al. , 2016). This is of particular interest in literary reading. However, little is known about the relationship between spatial processing for narratives and the phenomenological aspects of internal scene construction that interest literary scholars.

In this paper, I suggest that one way researchers can advance knowledge about spatial representations in literary reading is by looking at neurotypical and neurodiverse, and more specifically autistic, reader traits. Relevant traits distinctive to some autistic people include strong visual and especially visuo-spatial imagery (Souliéres et al. , 2011; Maróthi et al. , 2019), but difficulty in internal scene construction — the ability to generate spatially coherent scenes through mental simulation (Mullally, Hassabis and Maguire, 2012) — related to episodic memories, episodic future thinking and imagination (Lind, Bowler and Raber, 2014). Identifying readers with these traits and comparing them with readers who lack these traits may present several advantages, particularly in helping researchers understand the relation between spatial comprehension and spatial phenomenology (and whether they are dissociable) in literary narrative reading, as well as understanding what role spatial imagery plays in the generation of subjective states like narrative absorption (see Hakemulder et al. , 2017).

Aims and Methods of Investigation

For future researchers, one question that could be pursued is the extent to which spatial narrative phenomenology is dependent on spatial comprehension abilities. In this case, using readers who demonstrate differences in spatial comprehension abilities would allow researchers to consider whether, for example, strong visuo-spatial imagery, or weak internal scene construction, are associated with subjective differences in imagining literary narrative space. In order to determine comprehension differences in autistic and non-autistic readers, researchers could use a variety of measures used in spatial cognition and mental imagery assessments. They include, for instance, the Embedded Figures Test (Almeida et al. , 2010) and Mental Rotation tasks (see Conson et al. , 2022), for spatial cognition, and the Visual Imagery Questionnaire (Dance et al. , 2021) and the Object-Spatial Imagery Questionnaire (Blajenkova, Kozhevnikov and Motes, 2006), for visual and spatial imagery. For internal scene construction, researchers could rely on the Spatial Presence Experience Scale (Hartmann et al. , 2015) and the Spatial Coherence Index questionnaire (Hassabis et al. , 2007).

Another important question that could be asked is how readers with certain processing traits respond to spatial representations in literary narratives. This could be achieved by assessing the quantity and quality of spatial descriptions in a given text (either presented in full, or excerpted). Assessing the number of spatial descriptions in a chosen text or excerpt (see Gysbers et al. , 2004), the level of spatial coherence (Hassabis et al ., 2007), what spatial frame is adopted in the text (e.g. whether a scene is described from a first-person or third-person perspective) (Hartung et al. , 2016), and how spatial descriptions are organised in the prose — i.e. whether they begin with proximal objects to distal objects, reverse this, or change its order, in a visuo-spatial field (see Finnigan, 2013) — offer several ways of doing this. Combined with measures for evaluating visuo-spatial and internal scene construction abilities, researchers could predict the extent to which textual representations of space determine the quality of spatial imagery for autistic readers, in contrast to neurotypical readers.

Lastly, in order to understand the contributions both textual representations of space and spatial processing traits make to certain subjective states, researchers could borrow questions from the ‘Transportation Scale’ (Green and Brock, 2000), the Story World Absorption Scale (Kuijpers et al. , 2014), and the Immersion Questionnaire (Hartung et al. , 2016), and ask participants to respond to them after reading. An interesting question to pursue in this context is whether autistic people are more, or less, open to states like absorption through spatial imagery processing, and whether certain traits determine this.

References

Almeida, R. A., Dickinson, J. E., Maybery, M. T., Badcock, J. C. and Badcock, D. R. (2010). ‘A new step towards understanding Embedded Figures Test performance in the autism spectrum: The radial frequency search task’. Neuropsychologia , 48 (2), pp. 374-381. Redirecting.

Avraamides, M. N., Galati, A., Pazzaglia, F., Meneghetti, C. and Denis, M. (2013). ‘Encoding and updating spatial information presented in narratives’. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology , 66 (4), pp. 642-670. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2012.712147

Blajenkova, O., Kozhevnikov M. and Motes, M. A. (2006). ‘Object-spatial imagery: a new self-report imagery questionnaire’. Applied Cognitive Psychology , 20 (2), pp. 239-263. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1182.

Conson, M., Senese V. P., Zappullo, I., Baiano, C., Warrier, V., The LabNPEE Group, Raimo, S., Rauso, B., Salzano, S. and Baron-Cohen, S. (2022). ‘The effect of autistic traits on disembedding and mental rotation in neurotypical women and men’. Sci Rep , 12 (4639). The effect of autistic traits on disembedding and mental rotation in neurotypical women and men | Scientific Reports.

Dance, C. J., Jaquiery, M., Eagleman, D. M., Porteous, D., Zeman, A. and Simner, J. (2021). ‘What is the relationship between Aphantasia, Synaesthesia and Autism?’. Consciousness and Cognition , 89 (103087). Redirecting.

Finnigan, E. (2013). A cognitive approach to spatial patterning in literary narrative . PhD Thesis. University of Strathclyde.

Green, M. C. and Brock. T. C. (2000). ‘The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives’. Journal of Personality and Social Pscyhology , 79 (5), pp. 701-721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701.

Gysbers, A., Klimmt, C., Hartmann, T., Nosper, A. and Vorderer, P. (2004). ‘Exploring the book problem: text design, mental representations of space, and spatial presence in readers’. Seventh Annual International Workshop Presence 2004. Valencia: Technical University of Valencia.

Hartmann, T., Wirth, W., Schramm, H., Klimmt, C., Vorderer, P., Gysbers, A., Böcking, S., Ravaja, N., Laarni, J., Saari, T., Gouveia, F. and Sacau, A. M. (2015). Media Psychology , 28 (1), pp. 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000137.

Haenggi, D., Kintsch, W. and Gernsbacher, M. A. (1995). ‘Spatial situation models and text comprehension’. Discourse Processes , 19 (2), pp. 173-199. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539509544913.

Hakemulder, F., Kuijpers, M. M., Tan, E. S., Bálint, K. and Doicaru, M. M. (eds.) (2017). Narrative Absorption . Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Hartung, F., Burke, M., Hagoort, P. and Willems, R. M. (2016). ‘Taking perspective: personal pronouns affect experiential aspects of literary reading’. PLOS ONE , 11 (5). Taking Perspective: Personal Pronouns Affect Experiential Aspects of Literary Reading.

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Vann, S. D. and Maguire, E. A. (2007). ‘Patients with hippocampal amnesia cannot imagine new experiences’. PNAS , 104 (5), pp. 1726-1731. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0610561104.

Jahn, Georg (2004). ‘Three turtles in danger: spontaneous construction of causally relevant spatial situation models’ . Journal of Experimental Psychology: Language, Memory and Cognition , 30(5), pp. 969-987. 10.1037/0278-7393.30.5.969.

Jajdelska, E., Anderson, M., Butler, C., Fabb, N., Finnigan, E., Garwood, I., Kelly, S. Kirk, W., Kukkonen, K., Mullaly, S. and Schwan, S. (2019). ‘Picture this: a review of research relating to narrative processing by moving image versus language’. Frontiers in Psychology , 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01161.

Kuijpers, M. M., Hakemulder, F., Tan, E. S. and Doicaru, M. M. (2014). ‘Exploring absorbing reading experiences: Developing and validating a self-report scale to measure story world absorption’. Scientific Study of Literature , 4 (1), pp. 89-122. Exploring absorbing reading experiences: Developing and validating a self-report scale to measure story world absorption | John Benjamins.

Kuzmičová, A. (2014). ‘Literary narrative and mental imagery: a view from embodied cognition’. Style , 48 (3), pp. 275-293. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.48.3.275.

Lind, S. E., Bowler, D. M. and Raber, J. (2014). ‘Spatial navigation, episodic memory, episodic future thinking, and theory of mind in children with autism spectrum disorder: evidence for impairments in mental simulation?’. Frontiers in Psychology , 5. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01411.

Maguire, E. A., Vargha-Khadem, F. and Hassabis, D. (2010). ‘Imagining fictitious and future experiences: evidence from developmental amnesia’. Neuropsychologia, 48 (11), pp. 3187-3192. Redirecting.

Maróthi, R., Csigó, K. and Szabolcs, L. (2019). ‘Early-stage vision and perceptual imagery in autism spectrum conditions’. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience , 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2019.00337.

Mullally, S., Hassabis, D. and E. A. (2012). ‘Scene construction in amnesia: an FMRI study’. The Journal of Neuroscience , 32, pp. 5646-53. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5522-11.2012.

Pearson, J. (2019). ‘The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery’. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience , 20 (10), pp. 624-634. The human imagination: the cognitive neuroscience of visual mental imagery | Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

Pianzola, F., Riva, G., Kukkonen, K. and Mantovani, F. (2021). ‘Presence, flow, and narrative absorption: an interdisciplinary theoretical exploration with a new spatiotemporal integrated model based on predictive processing’. Open Res Europe , 1 (28). https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.13193.2.

Souliéres, I., Zeffiro, T. A., Girard, M. L. and Mottron, L. (2011). ‘Enhanced mental image mapping in autism’. Neuropsychologia , 49 (5), pp. 848-857. Redirecting.

Zwaan, R. A. and Oostendorp, H. (1993). ‘Do readers construct spatial representations in naturalistic story comprehension?’. Discourse Processes , 16 (1-2), pp. 125-143. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539309544832.