Speaker : Claire Woodward

Speaker : Claire Woodward

Affiliation : Department of Germanic Studies, Indiana University

Affiliation : Department of Germanic Studies, Indiana University

Title : Victimization Triggers Spontaneous Side-Taking in Narratives

Abstract : We study the effects of side-taking in narratives and find that when people spontaneously take a side for a victim, they do not remember the perpetrator well, assume the victim is the narrator of events, and judge the victim as more relatable and understandable. In ongoing narratives with escalations of violence between two characters, people remain highly committed to one side when they receive sympathetic background information about that particular character, but fail to maintain commitment without priming information. Our findings demonstrate how perceived disadvantages and victimization triggers side-taking in narratives and can potentially lead to ongoing polarization.

Long abstract

Long abstract

Victim narratives act as powerful motivators for spontaneous side-taking. In a wide range of cases people take sides spontaneously where they have no previous commitment to either side. We call this phenomenon spontaneous side-taking (SST) and suggest SST can occur when people observe a disagreement or conflict. In this paper, we explore how SST unfolds in narratives. While SST may lead to intervention in real world situations, we argue SST also occurs when no direct intervention is possible, such as in observing films, fiction, legal trials, sports, and debates. We propose that SST, though quick, can lead to long-term side-taking in the form of choice reinforcement, polarization, and coalition formation. These phenomena can then lead people to assume identities that serve to orient actions in social conflicts. To examine SST in narratives within the context of previous scholarship, we concentrate on three theories to narrative thinking: the Dyad Model by Wegner and Gray (2011, 2016), the Bystander Coordination Model by DeScioli and Kurzban (2009, 2013), and the Three-Person Model of Empathy by Breithaupt (2012, 2019).

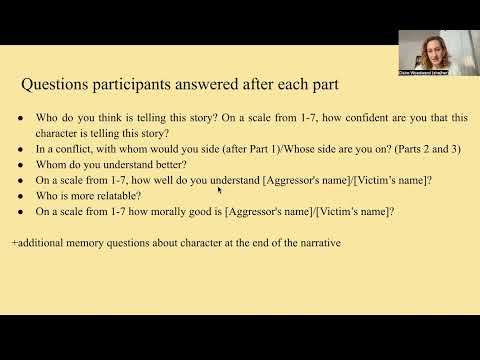

We designed two studies to help us explore how SST functions specifically in narratives. In both studies, participants read stories with two characters and are interrupted after each paragraph to respond to questions about the characters regarding side-taking preferences and associated confidence in their choices. In Study 1, the story presents a three-paragraph story with two characters that are first engaged in friendly interaction, until one morally harms the other. In Study 2, a five-paragraph story presents an ongoing conflict between two characters in which each character takes on the roles of both perpetrator and victim in each paragraph. Participants were collected through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, with a total of 127 participants for Study 1 and 322 for Study 2. Sample size was determined before any data analysis.

We find that when people spontaneously take a side for a victim, they do not remember the perpetrator well, assume the victim is the narrator of events, and judge the victim as more relatable and understandable. In ongoing narratives with escalations of violence between two characters, people remain highly committed to one side when they receive sympathetic background information about that particular character, but fail to maintain commitment without priming information. Our findings demonstrate how perceived disadvantages and victimization triggers side-taking in narratives and can potentially lead to ongoing polarization. Overall, our findings most support the Dyad Model and Three-Person Model.

We show that victimization triggers SST and leads to better memory of the victim. When

SST is maintained and prolonged over time, people have higher confidence in their choice than

when they previously switched sides. Our study has implications for an increasingly polarized

society, where many people believe they have the “right side.” Framing stories around victimhood leads to SST and may make SST more salient. While one may hope that SST trains flexibility of the mind not only to choose a side quickly in a conflict but also escape entrenched polarization by imagining other’s perspectives, our studies suggest that SST may stick and thus result in cemented side-taking and polarization. It seems that SST is connected to people’s unwillingness to give voice to the other side of an issue or conflict, demonstrated by current conversations about “cancel culture” and “safety-ism” strengthened by echo chamber effects in media consumption. Side-taking then becomes a side effect of existing within an echo chamber.

Similarly, our studies indicate that people are influenced by details outside of the current conflict.

The influence of the irrelevant but sympathetic background information in Study 2 and the

connection between side-taking and relatability in Study 1 indicate that side-taking may be largely based on relatability and emotion, not necessarily who most deserves support.