Speaker: Victoria Lagrange

Speaker: Victoria Lagrange

Affiliation: Indiana University

Affiliation: Indiana University

Title: **Pawn-Playing and Biased Empathy: Interactive Fiction Promotes Single-Perspective Empathy and Linear Fiction Multi-Perspective Empathy

Abstract (long version below): We present the results of two research using computational methods to detect emotions in book reviews in Korean, English, and Italian. In recent years there has been an increasing adoption of computational methods to simulate reading processes and the reception of literature. Here, we present a reflection on the relation between actual reading practices and their spontaneous verbalization in the form of reviews is needed. We make recommendations for the collection and analysis of data on digital reading platforms, showing how both the digital infrastructure and the context can strongly influence the results of research.

Long abstract

Long abstract

Participatory or interactive fiction is an increasingly popular genre that allows readers to choose how the plot should continue, in contrast to linear fiction that does not entail any choice made by the reader (Montfort, 2005). This medium has gained prominence with the internet, yet it remains an understudied genre of growing importance (Young et al., 2015). There are an increasing number of works of interactive fiction produced every year in the form of movies and video games (Netflix’s Black Mirror, Bandersnatch (2018), Dontnod Entertainment’s Life is Strange (2015), or Quantic Dream’s Detroit: Become Human (2018) to name a few) as well as literary interactive fiction.

In many respects, textual interactive fiction is similar to video games. Notably, players of video games and readers of interactive fiction both make choices that impact the development of the narrative, and some games, such as Quantic Dream’s Heavy Rain (2010) and Detroit: Become Human (2018) also involve perspective switches. While comparisons to video games are certainly attractive, we instead compare interactive fiction in our study with linear fiction, where readers and listeners often identify with the protagonist and thus co-experience the decision-making with the protagonist (Keen, 2006).

In interactive fiction, not only do readers passively slip into the shoes of characters, but they also take the wheel and make decisions for them. This has led some scholars and researchers to provide evidence that interactive fiction may be an especially well-suited medium to cultivate empathy (Hand & Varan, 2009; Riedl & Bulitko, 2012; Vázquez-Herrero, 2021), while others suggest that readers may be prompted to override the individual characters and instead project their own interests on the character and use them as avatars (Green et al., 2004; Wake, 2016; Green & Sestir, 2017). The debate about the role of empathy-related transportation in interactive fiction is ongoing and so far inconclusive.

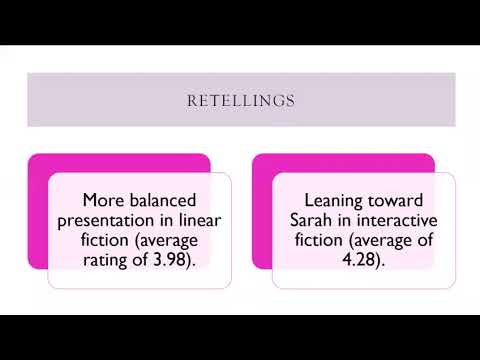

There is a central aspect of interactive fiction that has so far received little attention and that we suggest plays a major role for empathy. Readers often make decisions for more than one character; most of the time the decisions for one character also impact the well-being of other characters. In this study, we examine how this decision-making from the perspective of multiple characters impacts empathy toward each of the characters. In principle, it is possible that readers empathize with multiple characters; therefore, they make decisions that benefit each character (empathic concern) and are appropriately based on the characteristics of each one (perspective taking), thereby exhibiting “mobility of consciousness” (Breithaupt, 2019), to quickly adjust their mental framework to each character. It is also possible that readers select a favorite character, override the interests of other characters, and select story paths that will benefit their favored character, but not necessarily the character who is making the action. This second option we call “biased empathy,” meaning empathy that is focused on one character, person, or group while neglecting the wellbeing and perspective of others, as in empathic concern. We hypothesize that the activity of making choices in interactive fiction leads people to more strongly commit to a preferred character while neglecting others.

If our hypothesis is correct that interactive fiction increases biased empathy, it could potentially explain the conflicting findings in previous studies, because empathy could both be described as higher (for the preferred character), as similar to linear fiction (when considering all characters), or even as lower (for the non-preferred characters). As mentioned, none of the published studies on interactive fiction focus on side-taking and participants’ empathy with a specific character – which is why we focus on biased empathy in this study. By focusing on multiple perspectives and biased empathy in interactive fiction, we wish to draw a distinction between single-character and multi-perspective empathy. As a conceptual model, we hypothesize that interactive fiction with multiple characters leads to both a stronger commitment to a specific character and a deeper engagement with that character, especially with sympathetic protagonists, making details about them more salient (memory) and also increases empathy for them. On the flip side of this deeper engagement and stronger commitment, we hypothesize that other characters will seem of lesser importance (their self-interest will be ignored) and lower salience. The prediction of this conceptual model is that interactive fiction leads to biased empathy and pawn-playing.

To test this conceptual model, we developed a study based on a story that participants read either as a linear story or an interactive one with choices. We then measured their empathy, transportation, and learning. The story presents two main characters for whom we provided sympathetic background stories: a somewhat likable kidnapper who wants to keep the hostage for a utilitarian purpose and a hostage who wants to escape.

We ask:

- Does interactive fiction promote biased empathy for characters?

- Does interactive fiction promote biased actions toward characters (pawn playing)?