Speaker : Julia de Jonge, MSc

Speaker : Julia de Jonge, MSc

Affiliation : Department of Foreign Languages & Literatures at University of Verona; Faculty of Social Sciences at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; The Empirical Study of Literature Training Network (ELIT).

Affiliation : Department of Foreign Languages & Literatures at University of Verona; Faculty of Social Sciences at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; The Empirical Study of Literature Training Network (ELIT).

Title : “I’m not bad, I’m just drawn that way”: Immoral characters, aesthetic appreciation and sympathy in literary reading.

Abstract :

This paper argues it is not a fictional figure’s moral nature, as intended by the author, that affects the reader’s involvement with the story and the character, rather, readers’ moral judgement. The current experiment shows that while moral judgement of a character is mostly in line with intended character morality (e.g., doctor=good, Nazi=evil), moral judgement is a crucial aspect in reader’s aesthetic evaluation of a narrative and sympathy for its protagonist. Furthermore, an intercultural comparison was made between German and Italian readers showing that moral judgement differs among cultures when it comes to culturally sensitive figures (here, a Nazi-character).

Long abstract

Long abstract

While different reader-responses to narratives with moral vs. immoral characters have been attributed to multiple factors (manipulated character features [Salgaro et al, 2021]; moral disengagement [Krakowiak & Tsay, 2011; Shafer & Raney, 2012]), a causal element still seems to be missing: what causes different readers’ reactions – the constructed morality of the character or the perception of such morality by the readers?

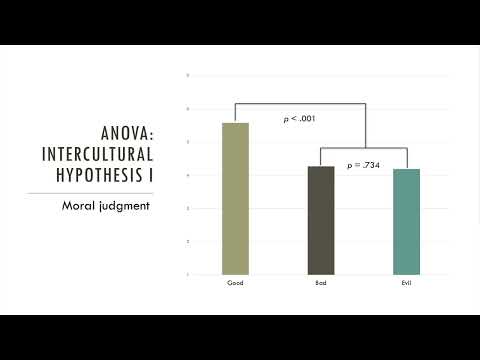

In this study, we compared three different moral characters, intended to be good (doctor), bad (corrupt prison guard), or evil (Nazi-officer). Moreover, perceptions of morality (i.e., moral judgement) likely differ among cultures, in particular when it concerns culturally sensitive characters, such as Nazis or Gestapos. Therefore, an intercultural comparison was also made between German and Italian readers of a text.

Previous research showed that fictional framing leads to a “suspension of moral judgement” (Vaage, 2013, p. 226-7). Because fictional figures don’t have real-life consequences, we would allow bad characters a much higher degree of moral disengagement. However, Salgaro et al. (2021) argue that the German readers in their experiment applied a so-called “reality check” to the Nazi-character in the story, that hindered readers to enjoy the fictional nature or the story itself. Such “perceived realism” seems indeed to play a role in the perception of literary characters (Krakowiak & Oliver, 2012). It is likely that a story presenting a Nazi-protagonist evokes a traumatic past for German readers who, thanks to education and Holocaust studies, might still feel this historic reality as close and related to their actual reality. However, one may wonder whether this would be similar for Italian readers, who had fascism in their historic reality but a different education and a different way of coming to terms with the history of World War II.

The current study aims to replicate and extend this study of Salgaro et al. (2021), using the same manipulated fictional narrative and testing similar concepts, yet including Italian readers. Perceptions of three fictional figures in passages from José Saramago’s Blindness (1996) were compared. The narrative is about a man who becomes blind and relays how the man navigates the world around him with his sudden loss of sight. Four sentences were manipulated to reflect the main character’s morality by referring to past moral actions. The story was manipulated to present either a good, a bad, or an evil protagonist: a doctor (good), a corrupt prison guard (bad), and a Nazi (evil). The experimental modification was limited to the insertion of a few sentences which refer in an indirect way to respectively good, bad, or evil deeds the protagonist had committed many years ago.

Results of our experimental study (N = 202) show that it is not a fictional figure’s moral nature per se that affects the reader’s aesthetic evaluation of the story and sympathetic involvement with the story character, but rather the moral judgement performed by the participants. The doctor-character received the highest moral judgement, the Nazi-character the lowest moral judgement. In line with these results, our readers sympathised the most with characters they considered morally good people, even if the character was intended as immoral (F (1, 197) = 29.056, p < .001, ηp2 = .129). This indicates that the intended character morality itself did not affect sympathy for the character, but rather the readers’ own moral judgement did. Moreover, the story with the Nazi-character was perceived as most aesthetically pleasing (F (2, 197) = 2.702, p = .070, ηp2 = .027), specifically when moral judgement for the Nazi-character was positive (F (1, 197) = 10.085, p = .002, ηp2 = .049).

We did not find any significant differences of character morality or moral judgement on character realism among the Italian readers. It might be that the Italian readers did not experience the “reality-check” as suggested by Salgaro et al. (2021) for German readers regarding the Nazi-character. Overall, scores for character realism are low (Mgood = 2.32, SD = 1.58; Mbad = 2.34, SD = 1.61; Mevil = 2.13, SD = 1.58). This might explain why Italian readers perceived the narrative as more aesthetically pleasant than the German readers. Because the potential “reality-check” did not occur among the Italians, this allows them to apply moral disengagement and enjoy the fictional nature of the narrative.

In all, the current study shows that the reader’s judgement of a character’s morality is crucial in the enjoyment of a fictional narrative and involvement with its protagonist, and that perceived character realism plays an important part in intercultural perspectives on immoral fictional figures. It is therefore important to highlight the divergence of reading experiences and lay out that moral nature is not an absolute value, but rather flexible. Implications for future research are thus that moral disengagement is a fundamental characteristic of literary reading and maybe one of the reasons for its fascination.

References

Krakowiak, K. M., & Oliver, M. B. (2012). When good characters do bad things: Examining the effect of moral ambiguity on enjoyment. Journal of Communication, 62(1), 117–135. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01618.x.

Krakowiak, K. M. and Tsay, M. (2011). The role of moral disengagement in the enjoyment of real and fictional characters, International Journal of Arts and Technology, 4(1), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJART.2011.037772

Salgaro, M., Wagner, V., Menninghaus, W. (2021). A good, a bad, and an evil character: Who renders a novel most enjoyable?. Poetics (101550). doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2021.101550.

Saramago, J. (1996). Cecità. Torino: Einaudi.

Shafer D. M. & Raney, A. A. (2012). Exploring how we enjoy antihero narratives. Journal of Communication, 62(6), 1028-1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01682.x

Vaage, M. B. (2013). Fictional reliefs and reality checks. Screen, 54(2), 218–237. doi:10.1093/screen/hjt004.