Speaker: Nicoletta, Chieregato

Speaker: Nicoletta, Chieregato

Affiliation: University of Bologna, Department of Education Sciences

Affiliation: University of Bologna, Department of Education Sciences

Title: Democracy, empathy, literature: encountering, discovering, listening to the other in formal educational contexts

Abstract (long version below): It is claimed that democracy requires empathy, and that empathy is fostered by literary reading. Starting from a critical analysis of these statements, the present study aims to understand if and how literary education can become an “empathy laboratory” and hence support democracy. A qualitative study carried out in schools explores how empathy occurs in reading experiences of 12-14 year-old students, and which factors facilitate or hinder such responses. Preliminary results reveal that empathy is a complex and dynamic process, requiring time, open discussions, teachers’ support, and sustained by specific texts features. Possible implications for designing literary education are proposed.

Long abstract

Long abstract

Within the wide spectrum of empathy definitions, the one closest to the democratic need to ensure legitimate collective deliberative processes – including the listening and legitimation of different and adverse points of view (Morrell, 2010) – is the phenomenological one (Boella, 2006, 2018; Stein, 2014; Zahavi, 2011, 2014). Phenomenology envisions empathy as the process of attunement with the other, to gain a better understanding of the interpretative emotional and cognitive categories informing his/her thoughts and behaviors, while keeping “the right distance”.

By creating opportunities for encountering, discovering and listening to the other, education is envisioned as an opportunity to enhance the empathic process (Council of Europe, 2018), possibly having literature as a powerful ally. In fact, literature is assumed to foster empathy and to represent a “form of cognitive-emotional apprenticeship” (Contini, 2011). Within the theoretical framework of a transactional approach to reading (Rosenblatt, 1978), literary narrative indeed offers the opportunity to de-familiarize perceptive, cognitive and emotional processes (Shklovsky, 1965), to “feel the other” (Boella, 2006) by – at least temporarily – taking his perspective (Cohen, 2001; Cohen & Klimmt, 2021), and to prompt reader’s reflection.

The purpose of the present paper is to share preliminary results of an empirical study carried out to explore how the relationship between empathy and literary reading might be exploited in schools.

The study aims to understand how young people between 12 and 14 years – at an important stage of their identity and psychosocial development process (Crone, 2016; Erikson, 1997) – experience literary narrative texts and interact with characters in their school contexts. Through documentation analysis, direct observation of reading classes (6 classes, 6 teachers, diversified by method and approach) and semi-structured interviews with teachers and with a sample of students (N=12), the research also investigates which elements appear to be significant so that the reading experience shapes (or doesn’t shape) up as an “empathy laboratory”.

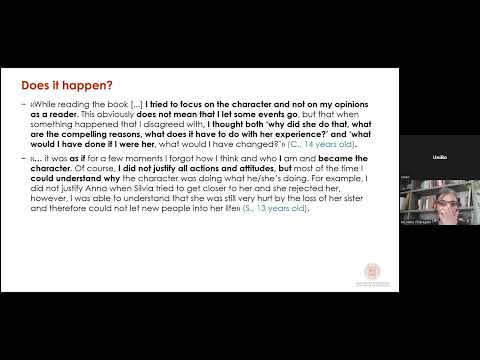

In a preliminary study (7 classes, 137 students) carried out to fine-tune the observation grid and the structure of the interviews, verbal data were collected through questionnaires and short written texts. Based on their thematic analysis, empathy seems to emerge as complex and dynamic process, characterized by the interaction of three constituents:

-

Acquiring awareness of one’s own perspective (“I was surprised by the different way of living […] and I thought how I’d have behaved in such a situation: it helped me better understand others’ points of view, but - above all - mine”), -

Entering the other’s experience and suspending judgment (“I identified with M. and I could feel his emotions […] If you look at the story from the outside, you might criticize his behavior, but if you step into his shoes, then his choices make sense”), -

Personal reflection (“of course, I don’t justify all behaviors, but […] I reflected on his way of thinking and mine, coming to a kind of conclusion ... also on different topics ... a new spark for my life”)

The recurrence of terms such as “at the beginning, […] then, when I started…”, “before, […] after”, “not immediately, […] but going on with the story” also suggests empathy is indeed a process that might require time. In addition to time, other supporting factors emerging from the youngsters’ words are: a) the presence of not-stereotypical and unpredictable characters (“a character who plays the though, then suddenly feels lonely, sad; that’s surprising”); b) the engaging and introspective language (“the story is compelling and it’s told in a way that made it easy to experience it ‘from within’”); c) the ability to imagine oneself as part of the story, thanks to a sensory approach to the text (“like a movie in my head”); d) reading aloud in class; e) writing tasks; f) group discussions; g) teachers’ counseling.

Possible obstacles could be instead:

-

Reading approaches focusing on discovering the “correct message” presumed to reside in the text, rather than on reader’s individual response to the story; -

Reading experiences designed to steer the reader towards directions that are defined correct a priori (normative moral education), instead of actually promoting a personal and responsible growth.

Preliminary evidences will be further investigated during the main study.

The study results appear promising and could effectively support the design of reading classes – aiming to train the empathic, hence the democratic, process – at school. Also, it is crucial to strive to ensure that reading experiences are real opportunities for all type of readers, not only for the “expert ones”.