Speaker: Melissa Seipel, Ph.D.

Speaker: Melissa Seipel, Ph.D.

Affiliation: Cornell University

Affiliation: Cornell University

Title: Audience Understanding of and Allegiance to Fictional Antihero Characters in Television and Film

Abstract (long version below): Qualitative analysis of three studies (focus groups, interviews, thought-listing) found participants used complex processes to understand and develop supportive, unsupportive, or mixed opinions and stances towards an antihero – a character with both good and bad traits and behaviors. Participants considered an antihero’s traits, states of mind, actions, relationships, and contexts as part of these dynamic processes. As story events unfolded and the nature of the antihero developed, participants often reconsidered previous judgments about the antihero. The results explained how audiences can sometimes root for an antihero to be successful and/or avoid negative consequences despite the antihero’s sometimes immoral behavior.

Long abstract

Long abstract

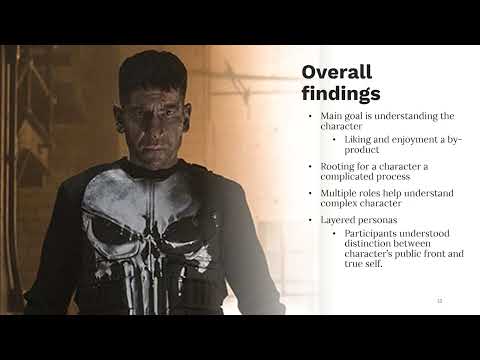

Three themes that emerged from the analysis indicated how participants understand the complexities and true nature of the antihero and determine the nature of their (the viewer’s) feelings, attitudes, and allegiances (sympathetic and/or antipathetic stances) towards the antihero character.

One theme indicated that participants drew on a character’s multiple roles to make sense of a character, compartmentalizing contradictory characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, etc., to an antihero’s multiple roles and personas (e.g. mother, sister, queen). Thus, mostly positive characteristics (loving, unselfish, etc.) might be assigned to one role, and negative characteristics (criminal, selfish) to another persona. Compartmentalization allowed participants to support participants in one role while simultaneously not supporting them in others. Similarly, participants reconciled mixed positive and negative character traits by recognizing the different “sides,” “layers,” or “depth” of an antihero’s personality, and evaluating antiheros’ various actions and choices as outward manifestations of the antihero’s inner-selves—with inner self/true nature most important. Participants often looked at the character’s actions and choices over time in developing an understanding of an antihero’s complex nature.

A second theme looked beyond the characteristics of the antiheroes themselves and considered contextual influences including relationships with other characters, context/circumstances, and an antihero’s background/development over the course of the narrative—sometimes allowing audience members to even excuse extreme behavior. These narrative elements that significantly contribute to an antihero’s thoughts, attitudes, and actions have been overlooked in most previous studies. The different dynamics of such relationships contribute to a multifaceted understanding of an antihero, informing participants’ complex expectations, judgements, and allegiances to the character.

The third theme focused on the audience member developing supportive, unsupportive, or mixed supportive/unsupportive stances towards an antihero. These judgements and allegiances appear to be influenced by a complex combination of factors, including an antihero’s actions and choices, how antiheroes compare to other characters or even themselves at various stages of their character arcs, and audiences’ developing understanding of and attitudes about the character as influenced by liking, attachment, sympathy/empathy, and relatability.

Most participants put in a great deal of effort to justify, rationalize, forgive, or forget an antihero’s negative actions or characteristics, especially once an audience member liked, admired, or invested in a character. Notably, audiences were not blind to the negative aspects of antihero characters and openly objected to the antiheroes’ immoral actions while still supporting them overall. The viewer’s desire for the character to succeed, improve, or simply survive allowed them to acknowledge, but work their way past, a character’s negative actions or characteristics. This mechanism that allowed an audience member to root for antihero despite questionable acts is an alternative to a focus on moral disengagement in earlier investigations.

While the findings support many aspects of extant theories and models, including the centrality of enjoyment, liking, moral judgements/moral disengagement, and influences on allegiance, many important new factors and processes emerged. Participants’ focus on understanding a character, suggests that liking and enjoyment – while important – may not be the most significant motivation for engaging with antiheros. Second, while morality was found to be a significant influence on participants’ allegiances, the findings suggest that when it comes to rooting for an antihero, moral judgements can be trumped by other viewer experiences such as liking, attachment, or investment in a character and the character’s story.

Finally, the findings of this project confirm that audience engagement with antihero characters is indeed extremely complex and deserves equally complex attention. The dynamic nature of engagement in particular makes it difficult to capture the full engagement experience as understanding and allegiances change with new information, developments, and audience experiences. While our project does not claim to capture the details of these types of dynamic processes, it was clear from participant discussions that their experiences with antihero characters did change over time, often dramatically. While difficult to conduct, studies that attempt to capture process are needed to better understand these dynamics.